Since I began my studies I have, perhaps unsurprisingly, become somewhat of a hypochondriac. The infamous ‘medical student syndrome’ is hard to escape when you spend every day reading about numerous conditions often with non-specific symptoms. A twinge of pain can transform into terminal cancer, a headache into meningitis. My favourite ailment so far struck when trying on a pair of shoes and finding them to be too small, this could not simply be a case of variations in shoes size between different shops, no no, I knew what this was, THIS was acromegaly, a hormonal condition causing gigantism with swelling of the feet and hands being an early sign. Never mind that this condition is extremely rare, this must be it, I left the shop and vowed to keep an eye on what I saw as my ever enlarging foot size.

Although the hysteria that often grips us as students may seem funny (as indeed it often is), there are times when we find ourselves needing to see a doctor and then we are faced with the question of whether to tell them that we are insiders in their world. Having had occasions when I disclose that I am a medical student and occasions when I haven’t I have seen how it can affect the discussion. One might assume that telling the doctor who is treating you that you somehow know what is going on would lead to a better outcome. Your instant camaraderie would foster the ideal relationship and help you decide together, as is all the rage these days, what the next steps should be. However, this has not always been my experience. On one occasion early in my studies I went to a walk in GP with lower abdominal pain that had been troubling me. On discovering that I was a medical student, he told me that what I was suffering from was paranoia about my health and that he could do nothing for me. ‘This is a common problem when we are students and don’t know enough about medicine yet’ he said and dismissed me. Yet three days later I was admitted to hospital and placed on IV antibiotics. After my five day stay I wanted nothing more than to waltz into his clinic triumphantly, brandishing my discharge letter with an ‘I told you so’ grin on my face. Needless to say I did not, but I have since that time hesitated to reveal my occupation, for fear that it will lead to a similar dismissal.

Yet, the times that I have kept this information to myself have also felt in some ways fraudulent. Now that I am slowly gathering the little tricks of the trade, the specific questions one should ask, the conversational tools we use to guide things in the right direction, I feel a bit like I am pretending not to speak the doctor’s language and am making them work unnecessarily hard by not admitting so. This feeling was most palpable when going to my GP and being seen by a new trainee. His desperation to follow the correct ‘structure’ (Calgary-Cambridge of course), his clunky questions about my ‘ideas, concerns and expectations’ and his assertion that we would ‘decide together’ all just sounded like jargon to me, a newly initiated member of the club. I wanted to cry out ‘I know what you are doing, I understand, drop the charade!’

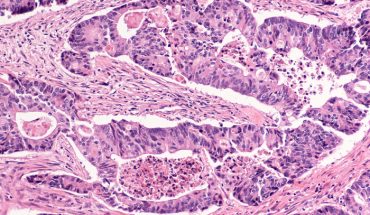

This may perhaps not seem like such a major question and indeed when dealing with minor ailments it is not. A lay person and a medical student with tonsillitis will probably end up with exactly the same antibiotics and advice. But what happens when serious illness strikes a doctor? Will they be treated differently? And perhaps more importantly will they be expected to make all the decisions? Having recently read the neurosurgeon Paul Kalinithi’s memoir ‘When Breath Becomes Air’, written whilst he was dying from lung cancer, I have been given a new insight into what is it to be a patient. The message that stands out to me in the book is that even a doctor, armed with more information than many patients, will need guidance. Kalinithi begins by being active in his treatment, deciding with his doctors what should be done, asking for all the information possible. But as his health fails he elects to cede his control to others, to experts. Sometimes knowledge is not enough. Even a doctor at the height of his career in one of the most rigorous and competitive fields would rather let someone else take decisions for him, such is the fear of making the wrong choice.

So much as I applaud the move towards shared decision making I am not hurrying to put myself in a position where I am expected to decide much about my own health. The next time I go to see a doctor, I might keep my studies to myself, even if it means sitting through a rather laboured demonstration of ‘communication techniques’, so that I have the luxury of not being expected to decide what should happen next.

- A Blind-Spot - 17th July 2016

- Being A Patient – Should I tell my doctor that I am a medical student? - 1st April 2016

- It’s a Sign – What a Textbook Can’t teach - 20th March 2016