Portraying Pregnancy: From Holbein to Social Media: A powerful new exhibition at The Foundling Museum explores changing representations of the pregnant female body over 500 years By Rebecca Wallersteiner.

Until the twentieth century, many women spent most of their adult years pregnant. Despite this, pregnancies are seldom apparent in surviving portraits. Curated by Karen Hearn, Portraying Pregnancy: From Holbein to Social Media the Founding Museum’s exhibition brings together rare portraits of women, who were depicted when they were pregnant (whether visibly or not) in a 500 year context. Through paintings, prints, photographs, objects and clothing from the fifteenth century to the present day, you can discover the different ways in which pregnancy was, or was not, portrayed and how shifting social attitudes have changed the depiction of pregnant women. More recently how images which often reflect increasing female empowerment, identity and emotion still remain highly charged.

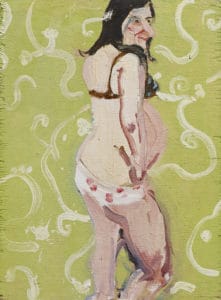

Chantal Joffe, Self Portrait Pregnant II, 2004 © Chantal Joffe Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro London Venice

One of the highlights of the exhibition is Holbein’s exquisite portrait of Thomas More’s daughter, Cicely Heron, which was sketched from life and a rare, frank observation of a pregnant woman. In many pre-twentieth century works in the exhibition, however, the sitter’s pregnancy has been edited out. For example, the mezzotint made after Sir Joshua Reynolds’s full-length portrait of Theresa Parker shows no visible sign of her pregnancy, in keeping with conventions of the time, despite reliable documentary evidence that by her second sitting in February 1772, Theresa was heavily pregnant.

Of particular interest is the maternity dress that Princess Charlotte wore for her portrait painted by George Dawe in 1817, the year she died in childbirth, both on loan by Her Majesty The Queen from the Royal Collection and the Foundling Museum’s celebrated painting by William Hogarth, The March of the Guards to Finchley, 1750, which features a heavily pregnant woman at its centre.

Other more recent highlights on display are Alison Lapper (8 Months), 2000, by Marc Quinn and Girl with Roses, 1957-8, Lucian Freud’s thorny portrait of his first wife Kitty and their stormy marriage.

G H Harlow, Sarah Siddons as Lady Macbeth, 1814 © The Garrick Club, London.jpg

Today, women with access to birth control can expect to plan if, or when, they become pregnant. Prior to the 1960s, many women would have experienced, between marriage and menopause, a number of pregnancies – and their daily lives might alter little for most of the gestation period. This is exemplified in a portrait of the celebrated eighteenth century actress, Sarah Siddons, shown in the role of Lady Macbeth, which she famously played up until the final weeks of pregnancy. Fear of dying in childbirth was very real and often justified. Until the early twentieth century, most births took place at home, often attended by family members, and consequently many women witnessed death in childbirth. Elizabethan and Jacobean portraits of visibly pregnant women, such as Marcus Gheeraerts II’s portrait of a heavily pregnant Unknown Woman, dated 1620, appeared in the same era as the ‘mother’s legacy’ text – in which a woman wrote a ‘letter’ for the benefit of her unborn child, in case she should not survive her confinement. An example is the manuscript that the well-educated Elizabeth Joscelin wrote in 1622 for the child she was carrying.

Marcus Gheeraerts II Portrait of a Woman in Red, 1620 © Tate

Maternal mortality is also powerfully represented by George Dawe’s 1817 portrait of the pregnant Princess Charlotte, the heir to the British throne, wearing a fashionable loose ‘sarafan’ dress, as well as by the actual surviving garment, displayed alongside it.

The Pre-Raphaelite artists painted pregnant women in their own social circle. Augustus John’s c1901 full-length portrait of his wife, Ida, must have seemed astonishingly transgressive to viewers at the time, as it clearly depicts her as pregnant. It was not until the late 20th century that pregnancy stopped being ‘airbrushed out’ of portraits. In 1984, the British painter, Ghislaine Howard produced a powerful self-portrait of herself as heavily pregnant. However the watershed moment occurred internationally in August 1991, when Annie Leibovitz’s photographic portrait of the actress, Demi Moore, naked and seven months pregnant, appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair magazine. This image was considered so shocking that some retailers refused to stock the issue. Nevertheless, it marked a change in attitudes and started the trend for more visible celebrations of pregnant bodies. The final photograph in the exhibition, by Awol Erizku, was commissioned by the singer, Beyoncé Knowles, who posted it on Instagram on 1 February 2017. Depicting Beyoncé pregnant with twins, veiled and kneeling in front of a screen of flowers, the image became the most liked Instagram post of that year.

This exhibition is the first of its kind and provides and provides an exceptional opportunity to examine contemporary issues of women’s equality, autonomy and health in a five hundred year context.

Portraying Pregnancy: From Holbein to Social Media is supported by Taylor Wessing, the Drapers’ Company, Norland College and the 1739 Club.

The Foundling Museum, 40 Brunswick Square, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 1AZ t. 0207 841 3600;

Open Wednesday – Saturday 10:00-17:00, Sunday 11:00-17:00, Monday closed Admission: Adults £10.50 with donation, Concessions £8.25 with donation.

The accompanying book Portraying Pregnancy: From Holbein to Social Media by Karen Hearn, is currently available from the Museum shop or online from publishers Paul Holberton

www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk

The Royal Collection – www.rct.uk/collection

- Dream Worlds a new exhibition in Cambridge - 14th December 2024

- “All Our Stories” a major new exhibition - 26th September 2024

- Dance yourself well - 23rd June 2024