A century ago it was wounded soldiers, rather than celebrities, queuing for the latest plastic surgery. The First World War saw the rise of terrible facial injuries, which left many patients afraid of what their families and friends would say when they saw how badly disfigured they were. However, thanks to the hard work and dedication of brilliant pioneering surgeons and anaesthetists who carried out long operations to reconstruct these wounded men’s badly injured faces, they could hope for a normal life.

‘The floodgates in my neck seemed to burst, and the blood poured out in torrents… I could feel something lying loosely in my left cheek, as though I had a chicken bone in my mouth. It was in reality half my jaw, which had been broken off, teeth and all, and was floating about in my mouth.’ John Glubb, hit by a shell fragment in August 1917.

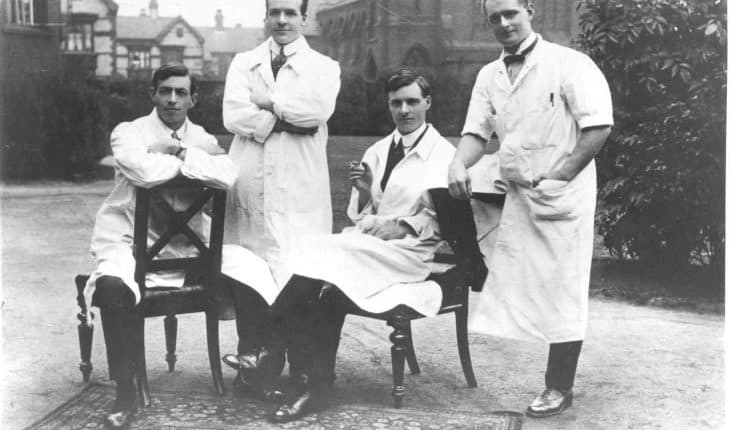

Located in the heart of London, the Anaesthesia Museum has curated a series of four temporary exhibitions honouring the work of doctors who gave anaesthesia and pain relief to the wounded during the First World War. The new exhibition, and the last in the series, ‘Brave Faces’, explores facial reconstructive surgery during and after the First World War and pioneers of anaesthesia in the field, Sir Ivan Magill and Dr Stanley Rowbotham, whose work enabled surgeons to develop new methods of facial reconstructive surgery, marking the dawn of plastic surgery as we know it today.

Until the First World War most battle injuries were caused by sword cuts or canon fire. Facial injuries were often of little importance to soldiers who felt lucky to survive a battle.

Until the First World War most battle injuries were caused by sword cuts or canon fire. Facial injuries were often of little importance to soldiers who felt lucky to survive a battle.

This all changed after 1914 as heavy artillery, machine guns, tanks, barbed wire and poison gas, created injuries of a severity and scale unseen before. Trench warfare resulted in a dramatic rise in the number and severity of facial injuries sustained by soldiers. Soldiers peering over the parapets of trenches frequently had their faces blown off when shells, filled with shrapnel, exploded. These new weapons were designed to cause debilitating injuries and tear through flesh causing twisting, ragged wounds and lost limbs.

It was difficult to treat facial injuries on the front line. Surgeons did their best working in harsh conditions at risk of being killed themselves. Most were untrained in plastic surgery techniques and stitched together gaping wounds without considering the amount of flesh that had been lost.

As injuries healed, the flesh tightened, stretching the face into an unattractive, contorted facial expression, like a grimace. Some injured soldiers were left with a gaping hole where their noses, or eyes used to be. Others, with broken jaws had to be nursed, standing up to stop them from suffocating.

The current exhibition ‘Brave Faces’ shows how the innovations of Dr Ivan Magill and Dr Stanley Rowbotham revolutionised facial surgery and gave hope to these men. Having served in France, in the Royal Army Medical Corps, during the First World War, in 1919, Magill was posted to Queen Mary’s Hospital for Facial and Jaw Injuries in Sidcup. This was a special military hospital with an international surgical staff undertaking reconstructive surgery of war wounds, which included the pioneer plastic surgeon Major (later Sir) Harold Gillies. Even though he had almost no practical experience in administering anaesthesia, Magill was the appointed anaesthetist. It was here he invented his famous technique alongside Stanley Rowbotham of delivering anaesthetic through rubber tubes placed directly into the patient’s trachea, rather than through a facemask. ‘Wide-bore intubation’ enabled surgeons to operate on the face and jaws without being impeded by anaesthetic apparatus which was essential during facial reconstruction.

Magill went on to become the leading exponent of anaesthesia for the developing specialty of thoracic surgery, and was an initiator and examiner for the Diploma in Anaesthetics in 1935. He devised many anaesthetic apparatus which have formed the foundation for much of the speciality. In this fascinating exhibition visitors will see the apparatus used in facial reconstruction at this time, and the many anaesthetic objects and apparatus designed by Magill himself, and the evolution of such objects over time.

Early forms of reconstructive surgery, including primitive nose jobs, are thought to have been carried out as early as 800 BC in India

Brave Faces: Powerful Stories of Facial Reconstructive Surgery during World War I, until 30 November 2018, at the Anaesthesia Heritage Centre, 21 Portland Place, London W1B 1PY tel. 0207 631 1650

- Dream Worlds a new exhibition in Cambridge - 14th December 2024

- “All Our Stories” a major new exhibition - 26th September 2024

- Dance yourself well - 23rd June 2024